Roumeika as the Defining Symbol of Greek Identity.

Shaitan Alexandra,

Temple University, Tokyo Campus

Historical Overview

According to Manuylov (2015), in 1763, during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762–96), Empress of Russia, the first Pontic Greek settlers of around 800 families arrived in the Caucasus Region. They worked the ore deposits on the northern border in modern Armenia. Subsequently, the miners founded new settlements in Transcaucasia [Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia] and the North Caucasus region in a migration that continued into the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1775, Catherine permitted Greeks from the Aegean Islands who had served in the Russian army as well as farmers from Greece, Bulgaria and Moldavia, to settle in Crimea. In 1778–79, Catherine assisted a group of Crimean Greeks to settle in Mariupol (aka ZHDANOV) and the surrounding area in modern Ukraine. These Crimean Greeks either spoke a dialect of the Turkish (URUM) language or Greek (Romeika Glossa). The two groups settled in separate areas in the same region.

According to the 2001 Ukrainian census, approximately 120,000 ethnic Greeks resided in the eastern region of Ukraine, known as Donbass, with the majority concentrated in the city of Marioupol and 32 surrounding villages (Blackwell, 2011; Topalidis, 2018). This population constitutes the largest Greek diaspora within the former Soviet Union. Despite their status as a minoritized community, these Greeks have preserved their cultural traditions for more than two centuries, with language serving as a central medium through which identity, belonging, and collective memory are negotiated. As Fishman (1999) argues, the intergenerational transmission of language is crucial for sustaining ethnolinguistic vitality, a dynamic evident in the enduring presence of Rumeika and Urum among the Greeks of the Donbass.

Linguistic Diversity

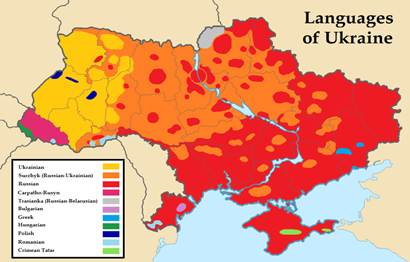

A defining feature of this diaspora is its internal linguistic diversity (Victorova, 2006). Some Greek settlers and their descendants speak Urum – a Turkic language – predominantly in 14 villages, while Roumeika – a dialect of Modern Greek – is spoken in 18 others (Gromova, 2009). The Roumeian population, speakers of Roumeika, migrated to Priazovye from Crimea in the 1770s alongside Ouroums, a Turkophone Orthodox group, and other Christian communities (Victorova, 2006). Here, linguistic affiliation functioned as a key marker of identity, distinguishing subgroups within the broader category of “Greeks.” In line with Edwards’ (2009) observations, language operates not only as a communicative resource but also as a symbolic boundary that delineates group membership and cultural distinctiveness.

Roumeika itself embodies the layered identity of the Roumeian Greeks. Scholars have highlighted its considerable structural variation, prompting the recognition of distinct varieties within the dialect (Baranova & Victorova, 2009; Pappou-Zouravliova, 1999). While some researchers argue that it originated in Pontos—a historical region on the southern coast of the Black Sea – Trudgill (2003) challenges this view, suggesting instead that Roumeika shares affinities with Cretan, Cypriot, and northern Greek dialects. These competing narratives of linguistic genealogy illustrate what Hall (1996) refers to as the “discursive construction of identity”: the search for linguistic roots becomes intertwined with questions of ancestry, belonging, and the imagined community of Hellenism.

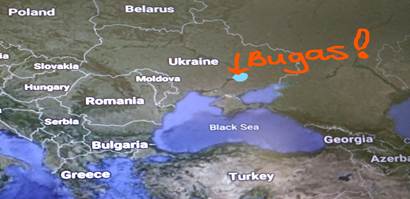

This presentation focused on Bugas, a village primarily inhabited by the Roumeian community, where Greeks constitute approximately 98% of the local population (1,456 individuals), according to the 2020 census of Bugas. Bugas (Ukrainian: Буга́с; Russian: Буга́с, romanized: Bugas; Greek: Μπουyάς) is a village in southeastern Ukraine, located in Volnovakha District, Donetsk Region. Previously known as Maksimovka (Russian)/ (Ukrainian: Маksimіvка) during the times of the Soviet Union.

Although demographic changes, including interethnic marriages, have introduced greater diversity, Greekness remains the dominant cultural identity. In Bugas, language is more than a means of communication- it is an identity resource. Within households and community gatherings, Roumeika remains the primary language, anchoring everyday life and embodying what Fishman (1989) describes as the “intimacy” of heritage languages: the affective ties that link individuals to family, community, and ancestral memory.

Modern Greek, however, has been systematically introduced into Bugas school curricula over the past two decades. This shift provides younger generations with literacy and fluency in the standardized national language of Greece, thereby strengthening symbolic ties to the wider Greek diaspora. As Edwards (2009) notes, language standardization often facilitates transnational identification, allowing local communities to position themselves within larger imagined collectivities. For Bugas Greeks, Modern Greek represents not just a practical skill but a symbolic resource, aligning them with global Hellenism and reinforcing a diasporic consciousness.

Modern Greek Versus Roumeika

Modern Greek:

Είναι μια όμορφη μέρα σήμερα /Eínai mia ómorfi méra símera. It is a beautiful day today/

Romeika: σήμερα ev καλό μέρα. /Simera en kalo mera/It’s a good day today.

Modern Greek: Τώρα βρέχει / tora vrehi/It is raining now.

Romeika: Τώρα pai βρ- ushi /tora pai vrushi. It’s raining now.

Some phrases in Greek/Roumeika

Καλημέρα/ Kalimera/Good morning/

Καλησπέρα / Kalispera/

Καλλιγραφία / calligrafia/ calligraphy

ευχαριστώ /efharisto/ thank you

σε αγαπώ / se agapo /sagapo/ love you

υγειά σας! /yasas/ Cheers/

με λένε / me lene/ my name is /

Λέγομαι /legome/I am called

το όνομά μου είναι / to onoma mu ine/ my name is

Current Situation

The younger generation of Bugas Greeks thus embodies a multilingual repertoire: they command Modern Greek, speak Roumeika and Russian in familial and communal contexts, and are fully proficient in Ukrainian, encompassing reading, writing, and oral communication. This multilingualism exemplifies the identity negotiations of Bugas Greeks, who navigate multiple linguistic worlds and corresponding identity positions. Roumeika affirms local and ancestral belonging; Modern Greek situates them within a transnational Greek identity; Russian functions as a post-Soviet lingua franca; and Ukrainian provides integration into the civic and political life of the state. As Hall (1996) emphasizes, identity is not fixed but continually reconstituted through discourse. In Bugas, linguistic practice demonstrates this fluidity: language both anchors a sense of heritage and provides the flexibility required to navigate shifting social and political landscapes.

Since 2024, however, Bugas has come under Russian administrative authority, introducing a new layer of political and linguistic transformation. Russian has once again been declared the official state language of the village, and all residents have been required to exchange their Ukrainian passports for Russian ones. In effect, Bugas’s residents are now permitted – indeed expected – to use Russian in official domains, reversing the previous period of Ukrainian linguistic dominance. This oscillation between state-imposed linguistic regimes has produced what local residents describe as a form of “linguistic and political ping-pong,” wherein their everyday sense of citizenship, belonging, and legitimacy shifts according to the prevailing authority. For many, the repeated demand to “change” their language of identification and civic affiliation has been deeply unsettling, generating feelings of instability and trauma. In this context, the Bugas Greeks’ multilingual identity is not simply a cultural resource but also a survival strategy, reflecting their capacity to adjust to recurrent political upheavals while still seeking to preserve their local and ancestral heritage.

In sum, the Bugas Greek community illustrates how language both reflects and shapes identity in multilingual settings. For Greeks born, raised, and living in Bugas, linguistic practice is not merely instrumental but central to self-definition. Language sustains heritage, forges transnational bonds, and enables civic participation, while also mediating the precarious and shifting boundaries of political authority. Their experience demonstrates how language is not only a marker of belonging but also a site of negotiation, vulnerability, and resilience in the face of geopolitical change.

References

Baranova, E., & Victorova, N. (2009). Roumeika dialects of the Azov Greeks: Linguistic variation and classification. Moscow: Nauka.

Blackwell, R. (2011). Ethnic minorities in Eastern Europe: Cultural continuity and change. London: Routledge.

Edwards, J. (2009). Language and identity: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fishman, J. A. (1989). Language and ethnicity in minority sociolinguistic perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Fishman, J. A. (1999). Handbook of language and ethnic identity. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Leave a comment